Language Skills: Can I talk to my horse by using my seat?

The dance is a poem of which each movement is a word – By Mata Hari

As well as using the legs and hands to give signals, we can also use our ‘seat’ and bodyweight. This can be very effective, but is an often misunderstood way of sending signals to the horse.

Firstly, it is important to sit in the correct part of the saddle (see the article on Feeling Safe in the Saddle).

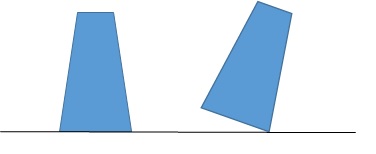

- A hollow back will mean that the pelvis is tipped too far forward at the top. This puts weight onto the front of the saddle and in some horses will ‘block’ the movement and cause it to slow down.

- A rounded back will mean that the pelvis is tipped too far back at the top (giving a ‘tucked under’ appearance). In some horses this will give a permanent aid to go forward, which will make it go faster or, alternatively, ignore a driving aid.

- Weight to one side or the other can make the horse crooked, and it will also make it difficult to use the seat to give signals for turns, canter strike-off, and lateral work (such as leg-yielding and shoulder-in).

What do you mean by using the seat?

To use the seat, first practice without the horse. There are two simple exercises that give the effect of using the seat.

1. Sit on a 4-legged stool with your feet placed on the ground to each side of the stool legs (or alternatively sit on the edge of a chair, but the lower seat does not give as good an effect). Sit up straight and hold your hands and arms as if you had reins. Tip the stool forward onto the front legs, but take care not to tip it so far forward that you fall off!

As you tilt the stool, close your eyes and feel:

As you tilt the stool, close your eyes and feel:

- the amount of effort that your lower back and seat muscles make in order to tilt the stool. Make sure you kept your upper body still.

- the way the your pelvis tilts as the stool tips; the lower part of your pelvis will tilt forward, then it will go back again as you let the stool return to the floor.

- the way that your weight goes down into your knees as the stool tilts.

Make sure that your head and upper body stay upright, without leaning back or forward. The action of tilting the stool is the same as that used in the saddle when both seat bones are brought into action.

2. Lie flat on the floor on your back, with your knees bent and your feet on the floor. While keeping your back flat against the floor, tilt your pelvis so that just your seatbones are raised off the floor. This should feel similar to tilting the stool.

Once you have done this, return the pelvis to the floor, then lift just one seatbone, (still keeping your feet and the rest of your back on the floor). This is the same affect as only using one seatbone while in the saddle. Practice this with each seatbone in turn, and with both together.

Once you have done this, return the pelvis to the floor, then lift just one seatbone, (still keeping your feet and the rest of your back on the floor). This is the same affect as only using one seatbone while in the saddle. Practice this with each seatbone in turn, and with both together.

Now, return to the saddle and practice the movements. Tilting the stool: this action will help to signal the horse to move forward. As you ‘tilt the stool’ ensure that your upper body doesn’t go forward or back, because only your pelvis should move. You should also feel that your weight is going down through your knees and heels (as it did on the stool). This will help your leg to stretch downwards as the aid is given (rather than ‘grip up’ and move up the saddle), and help your thighs and calves to close against the horse to help encourage the horse to move forward. Keep your feet under you or you will ‘fall off the stool’ (or unbalance the horse).

On a sensitive horse, this will be enough of on its own to increase speed or to signal a change of pace upward (e.g. halt to walk). On a less sensitive horse, this can be combined with an actual signal of the legs (using the calves inward) to give the ‘go’ signal.

Next, practice using one seat bone at a time. Unlike on the floor however, one seatbone will tend to go back a bit while the other one goes forward. The important thing is to remember that the upper body shouldn’t change position, only the pelvis.

Using one seat bone will not have a large effect on the horse on its own, but will help with circles and canter strike-offs, as well as some types of lateral work. As the horse performs these movements, its pelvis is angled so that the outer side of the pelvis is further back than the inside. For the rider to remain in balance with the horse, and to help its movement, the rider’s pelvis should follow the angle of the horse’s pelvis (while the rider’s shoulders should follow the horse’s shoulders).

Apologies for the poor image, but it should give you the idea.

Doing it wrong

Often when someone is told to ‘use their seat’ they think they are doing so, but their actions do not have any effect. Some common faults are:

- ‘polishing the saddle’ – the seat moves back and forward on the saddle without transferring the action through the saddle to the horse’s back muscles, so in effect the horse does not feel the action. This usually occurs when the rest of the rider’s body or legs are moving too. Solution; practice tilting the stool – only the pelvis should move.

- ‘rocking the body’ – the rider visibly rocks the upper body back and forward (which is readily seen by an observer). Again, the rider is doing a lot but the effect is not transferring through into the horse’s back muscles. Solution; practice both tilting the stool (while keeping the upper body still) and lying flat on the floor while lifting both seatbones together. When using a seat aid, an observer should have to watch very closely to see the rider doing anything.

- ‘driving the horse’ – the rider leans back and, although the horse may respond by going forward (as the rider’s pelvis will have tilted too), the rider’s weight is now behind the horse’s movement. The rider is, in effect, just giving one long seat aid (i.e. “Goooooooooooooooooooooooo”) rather than giving a signal that has a beginning and an end. Solution: keep the body upright while ‘tilting the stool’.

Remember that the seat aid should not be obvious to an observer; only the effect should be seen, so that it looks like the horse did it by magic.

Using the seat bones properly will signal the horse to move forward, but it is important to remember that this is only a signal and that, like other signals, the horse must learn what the signal means (although some sensitive young horses will automatically move forward from the signal). By combining the seat aid with the leg aid to start with, the horse will make the link between the two signals and learn what is required.

Note that it is common to say that the seat is used to ‘increase impulsion’ or ‘create more energy’. However, in effect the horse has to do this itself. The rider is only signalling that this is what is wanted. There is no way that the action of the seatbones on their own can pressure the horse to produce more energy if the horse is not interested or has not been taught what is required.

Slowing down and speeding up – using the seat and weight

When people perform the lunge exercise mentioned further down, many people are surprised by how easy it is to slow a horse down or speed it up by using their weight and the action of their seat. Unfortunately, we tend to focus on the reins to slow a horse down, but even a Thoroughbred off the racetrack, or a newly broken horse, will respond to the effect of the rider’s weight.

Leaning forward

In general, most horses will speed up when the rider leans forward. This is however something the horse has learnt, rather than something that is instinctive. For example, although a racehorse will speed up when the rider leans forward, a dressage horse may slow down instead, and many beginner’s horses will stop if they feel their rider gets out of balance. An unbroken horse may duck its head and spin, if the rider leans forward a lot, rather than speed up.

Riders tend to lean forward when they want to go faster, but they also do so when they feel nervous or insecure in the saddle. This can have the opposite effect to what the rider wants, e.g. if a horse speeds up because it is worried by something, and then the rider leans forward, then this gives some horses a signal to go faster. This is also made worse as the rider often lets their legs go back when they lean forward (another signal for the horse to go faster) and sometimes they also rotate their hand, which causes the whip to flick up onto the horse’s flank. So, without realising it, they may inadvertently give multiple signals to the horse to speed up without wanting it to.

Moving with the horse

As the horse goes into walk, we can feel a swing back and forward (and a little bit of sway from side to side) just because of the horse’s movement. We flow along with the horse’s movement by allowing our lower back to swing too, so that our seat moves with the saddle while our head and upper body stays relatively still.

The different paces of the horse have different amounts and types of movements, so we need to learn to adapt to the walk, trot, and canter to keep in balance with the horse. While learning these movements, it is easy to exaggerate the body movements e.g. watch a video of people at a trekking centre who have never ridden before; they will tend to rock their upper body as the horse moves rather than sitting still in relation to the horse. Now watch a video of a dressage rider, who looks as if they are part of the horse, not swinging in different directions. The same applies to jump riders, who only move their body when the horse is actually going over the jump, but sit in balance with it the rest of the time.

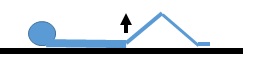

To see how effective your seat can be, get somebody to lunge you and tie a knot in the reins. If you can, drop the reins completely, but if you are not confident to do this then keep hold of the reins but make absolutely sure you do not have a contact with the mouth (the person lunging should control the horse). Then perform the following exercises:

- At walk: wait until the horse is walking steadily around in a circle.

- Lean inwards a little, with your weight towards your inside seatbone, and see what happens. The horse will normally start to cut in and make a smaller circle

- Now lean outwards and the horse will need to rebalance itself by stepping out. Note that the above two exercises may not work on horses that have been trained to maintain the circle regardless of what the rider does e.g. a riding school horse or pony club pony might just carry on doing a normal circle.

- At walk: sit quietly and feel how your body is moving slightly with the horse’s swing

- Stop moving with the horse: concentrate very hard on stopping your own body’s swing. Imagine that you are standing firmly on the ground and that no part of your body is moving. To stop moving with the horse, you will feel a lot of your muscles tense; your seat will stop swinging with the horse, your heels will probably sink lower, and your arm muscles will also stop the slight swing that follows the horse’s head movement at walk (even though you haven’t got the reins).

- If you do this, then it is very uncommon for the horse not to slow down or stop (lazier ones will stop). Even unschooled horses tend to respond to this.

- Ask the horse to walk on again by using the ‘tilt the stool’ aid, with a leg aid as well if needed.

- At trot: go into a steady rising trot, not too fast.

- To increase the horse’s speed,

- rise higher and sit more firmly back into the saddle (without ‘thumping’ down into the saddle and hurting the horse’s back). The increased time spent in the air and increased weight in the saddle will help increase the horse’s speed.

- rise faster. Think of a song with a fast rhythm and rise up and down in time with the song in your head. This will also increase the horse’s speed, with the horse usually taking quicker and shorter steps.

- To decrease the speed, do the opposite (remembering not to use the reins at all)

- Rise a very small distance and sit lightly in the saddle on landing. A good way to check how high to rise is to put the inside hand on the cantle of the saddle, which prevents you rising too high. Many people rise too high on a sensitive horse, not realising that this can make it go faster when they do not want it to.

- Rise slower; think of a song with a rhythm slower than the horse is going, or count slowly, and rise at a slower rhythm to slow the horse down. Even forward moving horses are very sensitive to the riders rhythm when they do this.

- Sit to the trot (holding onto the saddle if needed) and stop moving with the horse, as you did with walk. As with walk, it is very unusual for a horse not to slow down or even break into walk if this is done correctly, and some horses will stop.

- Another tip for slowing a horse down is to slant the top of the pelvis ‘forward’ so that the fork of your seat is pressing on the saddle rather than your seat bones. Sometimes, this will even stop a horse jogging when it is meant to be walking. However, it is important to return the pelvis to the normal angle afterwards, otherwise you could end up riding with a hollow back.

- To increase the horse’s speed,

Note that horses do not have to be trained to respond to the rhythm and weight of the rider. Horses will respond to the rider moving with them or against them (blocking the movement) even without training, and these can be used to help the horse learn the other signals that we use, as well as to improve the transitions and overall communication with the horse.