TO RUG OR NOT TO RUG – How hot is your horse?

“Happiness is a warm blanket.” – Charlie Brown

Quick Notes:

Horses are very efficient at controlling their core body temperature when the environmental temperature is between around 5 to 25 oC, and in winter they can acclimatise to a wider range (e.g. down to -15oC). Unlike humans, normal digestion in the horse’s hindgut produces a large amount of heat and therefore owners will feel cold when their horses do not. Many owners feel their horse’s skin, to see if it is warm, but this is not accurate and can lead to over-rugging, which can have negative effects on the horse’s health.

More Detail:

The horse has a core (inside) body temperature of around 37-38 oC and horses are very efficient at maintaining this when the environmental (ambient) temperature is within a certain range, known as the Thermoneutral zone (TNZ). This is the range in which a horse doesn’t need to adjust its physiology to be comfortable. Beyond this range, horses can change things like their metabolism and behaviour in order to maintain their core temperature and horses in the wild can survive in temperatures ranging from -40 oC to +58 oC.

In general, horses have a TNZ between around 5-25oC (UK) i.e. they can comfortably maintain their body temperature without feeling hot or cold if the environment is between these limits. During winter they can acclimatize to colder temperatures, so long as this change isn’t very sudden (it takes weeks for the horse’s hormones to adjust) and can still be comfortable down to -10--15 oC if they are dry and not in cold winds.

Can horse owners tell how warm their horses are?

Many owners judge how cold or warm their horses are by:

- Whether or not they themselves feel cold

- How warm their horse feels when they put their hand on its skin

- What temperature the weather forecast predicts

However, none of these methods are accurate when it comes to working out how warm a horse really is.

- Humans and horses differ in many aspects of how their bodies work, and this is one key area. Unlike humans, a horse’s diet includes lots of carbohydrates (from grass and other plants) that are digested by fermentation in the hind gut (large intestine and caecum). The caecum is equivalent to the human appendix but is much larger. It is about a metre long and can hold 20- 60+ litres in volume (about the size of 2 to 6 x 10 litre bucketfuls!). Fermentation of the forage produces heat, so the horse effectively has a large in-built heater inside its gut generating heat from its digestion; the more hay or grass it eats then the more heat it produces.

Therefore, it is much harder for a horse to stay cool than it is for it to stay warm. For this reason, it is highly unlikely that a horse will start to feel cold at the same temperature that a human does i.e. even if you have to put a jumper or coat on, it does not mean that your horse needs a rug at the same time.

- The horse maintains its core body temperature (inside) within a very narrow range. If this changes by more than 1oC then the horse experiences discomfort, and if it changes by too much then the horse dies e.g. the horse can die if it’s body temperature reaches 42 oC (an increase of 4-5 degrees from normal).

However the temperature of its skin (surface temperature) can vary across different parts of the body; can change often as the blood vessels constrict or dilate; and is cooler than the internal body temperature. For example, the temperature at the skin surface may be only 10 oC while the core body temperature is 38 oC i.e. the skin could be 28 oC cooler than the inside of the horse. It is normal for the skin temperature to vary. It can still feel cool even if the horse is warm enough in cold weather, because the horse will constrict the blood vessels near the skin and because the horse’s insulating fat layer is below the skin surface.

It is a myth that having cold ears always means that the horse is cold. The horse will have cold ears if the rest of the body is cold, but can also have cold ears when the rest of the body is warm (just as humans can). Difference in skin temperature a normal finding and is partly due to the horse’s efficiency in controlling its own body temperature. Therefore, it is not possible to tell if a horse is warm enough by feeling its skin (see below for why it is important that a horse’s skin should not feel too warm).

- As mentioned above, a horse is able to adapt to much colder temperatures than a human and therefore (unless the temperature drops suddenly or is extreme) the temperature on the weather forecast is not nearly as important to the horse as to its owner. Instead, the wind speed and the rainfall have a much greater effect, as a wet horse in a cold wind will lose heat at a much higher rate and will find it harder to stay warm.

How does heat loss work?

If a human or horse’s body is warmer than the temperature of the environment around it then heat will be lost, as heat travels down a temperature gradient from ‘hot’ surfaces to ‘cold’ ones (which is why your finger burns if you touch an element). This process is faster in some individuals than others and depends on a number of factors, one of which is insulation e.g. we all know that skinny people are more likely to ‘feel the cold’ than fatter people (because fat acts as insulation). Skinny horses find it harder to keep warm, while fat horses find it harder to keep cool.

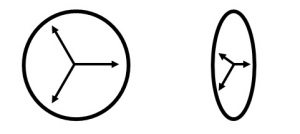

One of the factors that affects the amount of heat lost is the ‘body mass to surface area ratio’. This means that animals that are smaller or ‘flatter’ will lose heat faster than those that are larger or rounder in shape, and this is simply because the heat doesn’t have to travel so far to get to the surface. For this reason, a small foal will find it harder to maintain its body temperature than a large horse (also, a foal will usually have lower fat levels and therefore less insulation).

In cold air, the shape on the right has faster heat loss, as there is less tissue for the heat to cross.

Heat is produced all the time by bodily functions (called the metabolism). Some of the heat is used to keep the animal warm, but any excess must be lost to the environment, otherwise the organs inside the body get too hot and cells start to die i.e. the horse starts to ‘cook’ from the inside. Because the horse generates so much heat from its digestion, it must lose heat to the environment (unless it is fed poorly or it is in extreme weather conditions).

The horse can only lose heat to its environment if the air temperature next to its skin is cooler than the horse, so if the horse is hot at the surface of its body then it will be even hotter inside its core.

The horse has various mechanisms to keep warm or cool down (e.g. shivering, sweating, changing its metabolism) and these are controlled by the brain. The brain makes its decisions based on signals from both the inside of the horse and from its skin surface, which give information on how cold/ hot the horse is and how cold/ hot the environment is. These signals are crucial to allow the brain to make the correct decisions about how to control body temperature, and it is thought that over-rugging can interfere with this mechanism by changing hormone levels.

What does the horse do to control its body temperature?

Too cold: if the ambient temperature drops below the horse’s TNZ, then it will:

- Seek shelter. Owners are often surprised that their horse doesn’t use a shelter in cold weather (particularly snow), as they don’t realise how well the horse copes with cold temperature. However, most horses will seek shelter from rain or from rain combined with wind (and they will also seek shelter for shade when it’s hot). Groups of horses without shelter will huddle together and turn their tails to the wind to reduce its effect.

- Increase muscle tone/shiver. The horse can generate more heat by tensing its muscles, which then progresses to shivering as it gets colder. The horse can shiver for prolonged periods to maintain warmth, but must have enough food to support the extra muscle activity.

- Trap a layer of air within its coat by raising the hairs (piloerection). This helps insulate the horse against cold – it is a normal coping mechanism and does not mean that the horse needs to be wearing a rug, just that it is maintaining its body temperature. However, some owners don’t like their horses to look ‘fluffy’.

- Change its metabolism. As well as generating heat by shivering, the horse can breakdown stored energy supplies (e.g. fat), and also increase various other aspects of its metabolism to produce heat.

- Eat more. This is one of the key methods by which a horse can increase its body temperature.

- Move around more. This is not as an important mechanism as was once thought, as yearlings that are loose housed in cold climates don’t voluntarily move around much.

If the horse is not able to maintain its body temperature then it suffers from hypothermia, which can eventually lead to death.

Too hot: if the ambient temperature goes higher than the horse’s TNZ then it will:

- Sweat, dilate the blood vessels near the surface, and increase its respiratory rate. It will also move to shady or cooler areas and drink more. All of these mechanisms help the horse to lose excess heat.

- If the normal control mechanisms don’t work, then the heat load of the body will start to increase and these will be made worse by environmental effects (e.g. hot weather, high humidity). The horse can lower its metabolism and can eat less so that less heat is produced.

- In the next stage, if the high temperature persists and the horse cannot get relief by losing heat then the horse’s health and welfare will be affected. The core body temperature of the horse can increase (especially if the temperature changes are sudden) and things like growth and hormone levels are affected (see below).

- If the situation persists then the horse suffers heat stress and can die.

What happens if a horse has too many rugs on?

If you have ever woken up in bed feeling queasy from having too many blankets or leaving the electric blanket on, or felt dizzy and sick when entering a hot room in winter, then you will know what the early stages of heat stress feel like. Overheating leads to heat stress, which can:

- damage body cells and tissues

- affect the body’s immunity to disease

- decrease growth and healing

- cause electrolyte imbalances

- reduce thyroid gland function (and the ability of the horse to control its own body temperature)

- cause problems with sperm; embryo development; and lactation in breeding horses

- lead to obesity, particularly if owners also feed the horse more because the weather is cold

A paradox! Over-rugging can also affect the appetite, causing a horse to eat less, as well as the body’s ability to control its metabolism. So, some horses will LOSE weight when they are too hot all the time. The owner may think the horse is losing weight because it is ‘feeling the cold’, and so they put another rug on, making the situation worse. Therefore, some horses will PUT ON WEIGHT when wearing FEWER rugs, even if the owner thinks the weather is cold. Feeling the skin under the rug or looking for sweating are not reliable indicators of how hot the horse is, but overheating can be checked by taking the rectal temperature of the horse to see if it is normal.

Other more general disadvantages with using any rugs include:

- rubs and pressure points (particularly shoulders and withers). Rugs need to fit well and be checked often

- fungal or bacterial infections under the rug. Rugs should be removed daily and the horse groomed. The horse should spend some time (weather permitting) where the skin and coat is exposed to the air

- Injuries and entanglement. Ideally, horses should be checked twice daily but at least every day to ensure that rugs have not slipped or broken, and that the horse has not become caught up somewhere.

- Wet rugs can be worse than no rug, as they increase the heat loss from the body (via contact with a cold wet surface) and prevent the horses normal mechanisms working properly (e.g. can’t raise the hair coat for warmth). Check rugs after rain to ensure they are still waterproof.

- Vitamin D deficiency. The horse uses UV light to make Vitamin D within its skin, therefore covering too much of the horses skin then this is impaired. Artificial Vit. D supplied in the feed is not believed to be used as effectively by the horse.

A word on exercising the horse:

Most of the energy used up in exercise is given off as heat (80%). After exercise, the horse still retains a lot of the heat for a while (around 20%). In summer, this can be a problem as it is easy for the horse to become too hot. In the winter, this can be beneficial and help to keep the horse warm, but the cooling down period becomes very important.

If the horse has undergone moderate exercise (enough to get it hot and sweaty) then it is important to allow it to lose this extra heat gradually. Piling too many rugs on immediately the horse stops can be detrimental, as the horse will often be ‘steaming’ after exercise in winter – think how you would feel if you were really hot and sweaty and someone forced a jumper and coat on you.

However, it is also important that the horse does not get chilled by not rugging soon enough (especially if clipped) or by being damp from sweat and exposed to drafts or cold winds. The horse’s muscles can also develop cramps if hot muscles get cold too quickly.

In general, it is unlikely that a horse will get too cold in the first ten minutes following exercise, but there is no hard and fast rule of when and how to rug after exercise. It can take up to an hour for a horse to cool down after heavy exercise. Generally walking the horse in hand with a cooler on (designed to draw moisture away from the body without being too hot) can help reduce the temperature, and drying the horse (e.g. rubbing with handfuls of straw/ towels) can help warm the horse and prevent chills.

Although the horse can also acclimatise to being too hot, it is harder for a horse to cope with heat than cold and worst of all are sudden changes e.g. if a horse is over-rugged and has these removed to stand around in the cold at shows, or if a horse in the field loses its rugs in bad weather.

So, is rugging necessary?

There are many reasons to rug a horse, and these include:

- Keeping a horse clean. Although this isn’t necessary for a horse’s health, it can be an important factor in the practicalities of keeping a horse and riding it in modern society where time can be a limiting factor.

- Keeping the coat shorter and smoother for showing (or similar reasons). Again, this is a lifestyle choice for the owner rather than a welfare issue for the horse, but ultimately the horse has to meet the owner’s needs to be useful.

- Clipped horses. Removing large amounts of the horse’s winter coat reduces its ability to keep warm by about a 5oC margin i.e. it will feel cold sooner. This can be countered by feeding the horse larger amounts of forage, to generate more heat.

- Wind and rain (in horses not stabled). As mentioned above, the horse can be comfortable in low environmental temperatures if it is dry. Wet windy conditions cause a large ‘wind-chill’ factor, which makes it harder for the horse to maintain its body temperature. In winter, the wind-chill factor is sometimes mentioned in the weather forecast and can make temperatures considerably colder (e.g. by 5-10oC). Again, this can be countered by feeding the horse more, although a field shelter will provide shelter too.

- Sick horses. Horses that are ill are less capable of maintaining their own core temperature, particularly if they are eating less than normal. Some muscular problems also benefit from the horse being kept warm.

- Very old and very young horses (< 1yo) can also have problems maintaining their own body temperature in cold weather. In foals, this is partly because of their body mass to surface area ratio (see earlier).

- Being too cold also increases a horses risk of getting diseases

Note that it is usually healthier for a normal horse to be provided with shelter and extra forage (hay etc.), which also helps its digestive tract, rather than to use too many rugs. The amount of forage needed is often less than people think (see below) and rugging to ‘save on feed costs’ should not be a key reason for rugging.

Rule of thumb for rugging in winter (UK, not extreme weather)

Based on recommendations by leading researchers into equine thermoregulation

The average stabled horse in good condition, not clipped, should need no more than:

- One padded rug if the stable is insulated

- One padded rug and an underblanket (e.g. wool next to the skin) if the stable is not insulated

- Extra feed as the temperature drops below the lower limit of the TNZ

Depending on whether a horse is clipped, rugged, or stabled, an extra 0.2% - 2% of energy is needed per 1oC drop in temperature below its TNZ .

Horses in the paddock (or stabled) in full winter coat can maintain their body temperature without problems if they are dry and sheltered from the wind (with sufficient feed), so a field shelter is a good idea. Wet and windy conditions increase the need for rugging and for extra feed (as they cannot seek shelter and new grazing in the same way as a horse in the wild). Horses in the wild will also store body fat during summer and use this to keep warm during the winter.

However, if the daytime temperature is warm (above 20oC) then it is important to remove heavy rugs, as the horse can experience problems with excess heat. Because a horse adapts to winter temperatures, the upper limit of its TNZ is also lower; therefore, a horse adapted to an average temperature of 0oC can feel too hot when temperature is above 10oC! It is common to see owners in light shirts or t-shirts putting several rugs on their horse, either stabled or in the paddock, which can become a welfare issue.

To sum up:

Do horses have greater problems keeping cool than keeping warm? Yes

Can owners feel cold when their horse isn’t? Yes

Is skin temperature a reliable indication of how warm a horse is? No

Will extra food make a big difference to a horse’s warmth? Yes

Should I worry if my horse is out in the snow, but well-fed and dry? No

Does over-rugging cause health problems? Yes

Does under-rugging cause health problems? Yes

If my horses ears feel cold, does this mean he always needs an extra rug? No

Unless a horse is unwell:

If a horse is sweating it is too hot

If a horse is shivering it is too cold

If it is NOT sweating OR shivering then it:

- May still be too hot or too cold. For example, horses that haven’t acclimatised to hot weather can stop sweating even though heat stressed. Hypothermia is when the body is very cold and shivering no longer occurs.

- May be coping within its physiological limits e.g. dilating the blood vessels near the skin’s surface releases heat, whereas raising the hairs of the coat (making the horse look ‘fluffy’) traps air and decreases heat loss.

- May be comfortable and within its thermoneutral zone, regardless of whether its owner feels too hot or too cold.

The best method of finding a horse’s core temperature is by taking its rectal temperature (though note that this can vary for different reasons).

Do not rely on putting your hand under the horse’s rug!