LANGUAGE SKILLS - How well do we talk to our horses?

"The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place." - George Bernard Shaw

NB: This article should be read after FEELING SAFE IN THE SADDLE (click the link on the article page).

Essentially, horses communicate with each other via:

- body language (e.g. ears laid back)

- vocal sounds (e.g. neigh/ whinny)

- scents (such as pheromone messages in urine and faeces)

- touch (e.g. scratching each other near the withers).

Humans can mimic some of the horse’s own language, e.g. scratching near the withers will reduce the heart rate whether it is done by another horse or a human. However, when we ride a horse we need to communicate by touch in a different way and for this we use signals called “aids”, as in an ‘aid to communication’.

The horse is born with the ability to learn and understand horse language and they are also readily able to learn the signals we use to ‘talk’ to them. So, why is there often confusion between horse and rider?

Reasons include:

1. The horse has not been ‘taught’ the language i.e. they don’t know the aids. For example, a horse has to learn that pressure by the legs means that the rider wants it to move forward, or that a rein signal means slow down.

- The horse has been taught a different signal language to the rider i.e. they have learnt different aids (or different versions of the aids). For example, the horse may have been taught to strike-off in canter from the inside leg aid, while the rider has been taught to use the outside leg aid. Alternatively, the horse might have been taught, say, Western while the rider knows the English style. Horses can learn more than one ‘language’ e.g. they can readily learn both Western and English styles, but they need to be taught both languages, just as we need to be taught, say, French and English.

For the above two examples:

- Imagine you are in a foreign country but you don’t know the language; what would you do if someone said to you “hable frib masst cllfredl!” You wouldn’t have a clue what this meant.

- What would you then do if someone said it louder and repeated it? “HABLE FRIB MASST CLLFREDL!” You might realise that the person was trying to tell you something, but you still wouldn’t know what it was.

- What if they then started yelling at you or hitting you for not doing what they said? Unfortunately, this happens with horses a lot; the rider thinks the horse should already know the ‘language’ but the horse has not been taught it.

- The rider has not been taught the language, or cannot use it properly i.e. they don’t know what the aids mean or how to use them, and/or they cannot give the aids correctly.

- If you know a few words of a foreign language then you might be able to make yourself in some circumstances (e.g. you could tell a taxi driver ‘go’, ‘stop’, ‘turn left’) but it would be very difficult to have much of a conversation with anyone!

- The same occurs when a horse and rider don’t understand much of the language. If neither you or the horse know a lot of ‘words’, how would you say “slow down and put more weight onto your hindquarters ready for a turn to the left, while keeping a soft contact with my hand and bending to the left”?, or “lengthen your stride and increase the energy levels because the jump coming up has a big spread”?

In reality, some “conversations” between horse and rider are limited to ‘go forward’, ‘slow down’, ‘stop’, and ‘turn’. This is perfectly adequate for many types of riding, particularly with a co-operative willing horse that is used for hacking, however it has limitations.

In some sensitive and high-spirited horses, simple instructions may not be enough to control and guide them and problem behaviour can develop (e.g. beginner riders giving signals a horse does not understand). Uncooperative horses are also likely to develop bad behaviour. Higher level competitions need a greater degree of communication, whether it be adjusting the striding for a jump or adjusting balance and position for something like dressage.

Horses that have been trained to a high level (i.e. that are used to the rider using specific signals) can become confused if the signals are not what they are used to. For example, if the rider’s leg slips back by mistake the horse might think they mean to move sideways, yet the rider might get annoyed with the horse for doing this. If this happens too often then the horse may then either get upset and misbehave (e.g. buck, nap, rear etc), which the rider interprets as naughty; or ‘switch off’ and stop listening to the riders signal, which the rider interprets as lazy.

However, these naughty and lazy horses were really just trying to do what they were taught. Imagine a child that tries to help the teacher but is told off for doing so, or a person at work who thinks they are doing the right thing but whose boss is constantly finding fault. It is easy to see that if you do something that you think is right, but don’t get rewarded for it, then you might get frustrated, confused, or (if a child) disobedient. If this happens to us then we can sometimes work out what went wrong, but a horse doesn’t have the mental ability to do this; they might work it out by trial and error (called ‘operant conditioning), but they are more likely to be naughty or lazy depending on their personality.

So, now we know why it is important that both our horses and ourselves learn the same language, how do we do this?

In effect, a riding instructor is a ‘language teacher’ (along with a personal trainer, coach, psychologist, mentor, etc.) and can help translate between you and the horse, as well teach you both the same language. However, if you can’t afford a language teacher, you can learn a language and teach your horse to understand you (or vice versa) to a certain extent on your own.

LANGUAGE – the first words

Let’s start with ‘go’.

Horses are (hopefully) taught to go forward to one or more signals before a rider gets on their backs for the first time (e.g. by lungeing/ long-reining/ round pen or similar). This usually involves the trainer saying ‘walk-on’, ‘trot’, clicks with the tongue etc. Because these are human words, by the time you get on the horse you should be able to tell it to ‘go’ in some form or another (assuming you didn’t buy the horse unbroken from, say, Germany or France; in which case you might need to learn a few words of that language first!).

But, we want the horse to go forward from a leg signal, not by using words all the time.

We all know that if you kick someone hard enough they will move away from you (if they can). If you kick a horse hard enough it will move (either forwards, sideways, or backwards). After a few efforts, it will learn that if it moves forwards when you kick then you will stop kicking. WOW – did I just teach my horse the first word of its new language? Well, in a way. However, kicking is like shouting and we don’t want to have to shout at our horse all the time. We also don’t want to get our horse anxious and stressed in the process, although unfortunately this is how some horses are taught. How would you feel if your language teacher walked up to you and started shouting in a foreign language?

So, is there a better way?

Of course there is. Your horse already knows how to go forward when you ask it to. It can quickly learn to link this to a signal from your leg ‘asking’ it to move forward.

- Imagine you are being taught a game where you have to follow someone else’s instructions to find the treasure (reward). If they held up a blue card every time they said ‘walk’, and a white card every time they said ‘stop’, then you would soon associate these non-verbal signals with what they wanted you to do. So, if they stopped saying the words, you could still follow their other signals as you would have learnt what they meant and, after all, you really want that treasure! (we’ll come back to ‘treasure’ for the horse later).

Firstly, we have to decide what signal we are going to link to the word ‘go’. All we know so far is that we don’t want it to be a kick (too much hard work to yell all the time and we don’t want the horse to get upset or start ignoring us). You can teach a horse to link any signal to going forward (e.g. tap with whip, or even patting it behind the saddle); the horse doesn’t care what you use so long as it isn’t confused or stressed. However, it is best if your horse knows the same language that other horses learn, so that it can ‘understand’ a different rider. For example, it is no good teaching someone a ‘made up’ language then sending them off to work in, say, China. So, what word/s do most people use?

‘Go’ = a squeeze or nudge inwards with the legs. - Sounds simple doesn’t it?

But, where do you squeeze, how hard should you squeeze and why do confusions still occur?

Image courtesy of: Free diagram samples, available at: http://jb004.k12.sd.us/my%20website%20info/PICS/labeled_muscles_of_the_lower_leg_2.jpg

Image courtesy of: Free diagram samples, available at: http://jb004.k12.sd.us/my%20website%20info/PICS/labeled_muscles_of_the_lower_leg_2.jpg

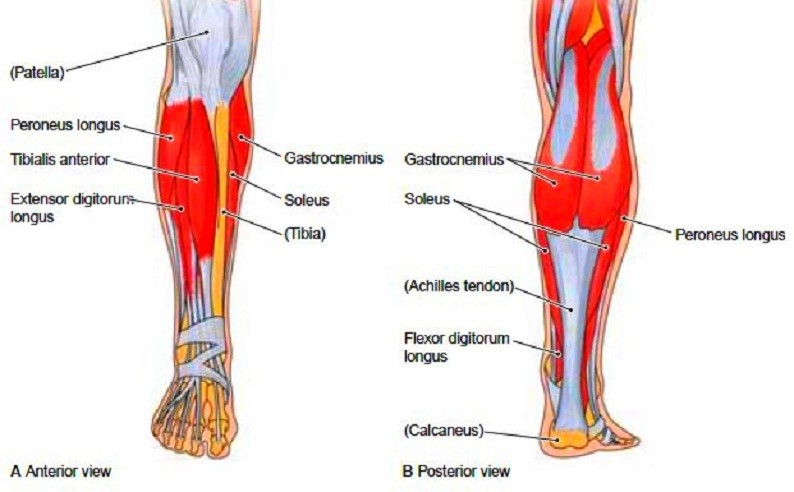

Look at the diagram and find the words ‘Gastrocnemius’ and ‘Calcaneus’ (don’t worry about trying to remember the words, they are just the names of the muscle and bone they point to).

- CORRECT – use the muscles on the inside of your leg to give an aid. For the ‘go’ aid, the action is a short squeeze inwards (toward the body of the horse) with both legs used evenly.

- Note that if you have your heel down, this muscle will be firm and give a clear aid

- If you have your heels up, then the muscle will be slack, and the aid will not be as effective

- If your legs are not in the correct position, then it is unlikely that the aid will be clear to the horse

- WRONG – many people don’t get a response from a proper leg aid, so they use their heel instead, but this is like shouting at your horse. Once you start ‘shouting’ it is hard to stop. The horse is not ‘deaf’ as such, so the reason it doesn’t respond to a leg aid is because it either doesn’t know the language, or has ‘switched off’ and ignores the leg aid (to correct this, the horse needs to be re-trained).

- If you have to keep kicking your horse with your heels then it will eventually become less and less sensitive, so that you will have to kick even harder.

- Using your heels puts your leg in the wrong position, therefore it upsets the balance of your seat (and the horse) and means that the leg cannot be used to tell the horse to straighten its hindquarters or to go sideways.

What else must happen to make my horse go?

When teaching the horse initially, the leg aid is linked to the words that the horse already knows e.g. "walk" + leg aid = move forward at walk. Eventually the horse makes the association and the leg aid can be used on its own.

In a trained horse, the leg aid should have the same effect. However, if the horse has become insensitive to the leg aid, and /or is reluctant to obey, then tapping with the whip will reinforce the leg aid. Do not get into the habit of giving harder and harder leg aids, as this will lead to kicking. It is important to give the horse a chance to respond first though i.e. do not use the whip before the horse has had time to react to the leg aid. If the horse ignores this, then it needs to be re-trained by someone more experienced.

Usually it is not enough to just use your legs, as you must also give with your reins. Rein aids will be covered in another article but essentially:

- If you pull on the reins at the same time as using your legs then the horse will either go upwards (as the energy has to go somewhere), or fight for its head, or become confused and upset, or ignore you and become dead to either the rein aid or the leg aid or both.

- Spirited horses tend to get upset

- Quieter horses tend to get lazy

- If you give away the reins completely, then the horse will go forward and ‘do its own thing’. This may be what you want anyway, or the horse may choose to go too fast, head in the wrong direction, or not be ready for your next signal.

- Try to give with the reins enough to allow the horse to go forward, but keeping a light contact (as if you were lightly holding someone’s hand).

But my horse is highly strung; it is always keen to go forward, so I don’t need to use my legs!

This is a common misconception, and usually leads to the rider hanging onto the horse’s mouth.

- WRONG – when the rider ‘gives with the reins’ (lightens the contact or gives a loose rein), the horse moves forward or speeds up.

- Giving the reins should indicate to the horse that it can stretch its head and neck forward (but not up) and/or relax.

- CORRECT – the horse waits for the rider to give a leg aid then goes forward or speeds up when the rider asks.

It is VERY IMPORTANT that all horses are taught to go forward when a leg aid is given, and not by release of the reins. If the horse is ridden only or mostly by rein aids, then it can lead to the horse:

- fighting for its head

- leaning on the bit

- rearing

- tucking its nose into the chest with no contact

Is this all that my leg aids do?

‘Go’ is just one word that you can use for communication. Depending on what other parts of your body are doing, your legs can also ask your horse to:

- swing its quarters to the side

- go side ways

- straighten its body

- take longer steps

- go backwards

- perform smoother transitions downwards

- and lower its head (YES – this is NOT A TYPO – pulling on the horse does not cause it to lower its head, but using your legs can).

These will be covered in future articles, but our next article will cover ‘stop’.

Back to the top of the page

Or, click the link below to return to the articles page.